Think for Yourself: Why Independent Research is Key to Your Health Journey

Published 01/15/2026

Table of Contents

- Why You Should Never Surrender Your Health to Blind Trust

- Authority Bias in Action: Learning from History and Experience

- RDA: Recommended (or Ridiculous?) Daily Allowances

- Food as Medicine: Ancient Wisdom Meets Modern Science

- Becoming Your Own Health Researcher – An Empowered Consumer

- Conclusion: Bridging Wisdom and Evidence for Great Health

- Sources

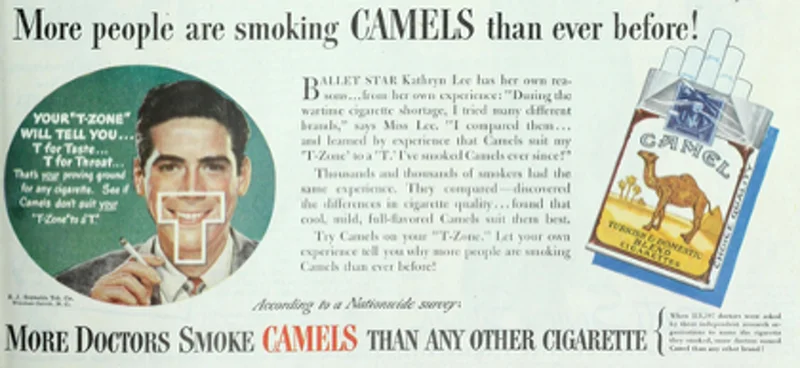

Imagine a time when doctors proudly endorsed cigarette brands. In the 1940s, glossy ads showed physicians in white coats proclaiming "More Doctors Smoke Camels than Any Other Cigarette!". It's jarring by today's standards – a stark reminder that even trusted authorities can get it horribly wrong. This historical oddity sparks an essential question for anyone on a health journey: how much should we really trust the "experts" and companies in charge of our health? In a world where pharmaceutical advertisements fill the airwaves and supplement marketers flood our feeds, it's more important than ever to do our own homework. Welcome to a conversation about taking charge of your well-being, the Ancient African Secrets way – with warmth, wisdom, and a healthy dose of skepticism.

In this article, we'll explore why independent research is a must when evaluating pharmaceuticals, supplements, and plant-based remedies. We'll unpack the concept of authority bias – our tendency to trust doctors, nutritionists, and officials without question – and see how it can lead us astray. We'll dive into the debate over Recommended Daily Allowances (RDAs) for vitamins and minerals, highlighting eye-opening insights from Bill Sardi's The New Truth About Vitamins & Minerals. (Spoiler: You may be surprised at how low those daily vitamin recommendations really are, compared to what emerging research suggests.) And since Ancient African Secrets is all about holistic wellness, we'll reconnect with the ageless idea of "food as medicine." For millennia, cultures – especially across Africa – have used plants and foods as healing tools, and science is finally catching up to why that works. Along the way, we'll include credible sources, a clear structure, and even a few visual aids (from research charts to vintage ads to vibrant food photos) to enrich this journey. So grab a cup of herbal tea and settle in – let's empower ourselves with knowledge and story.

Why You Should Never Surrender Your Health to Blind Trust

We all want to trust the medicines we take and the advice we receive. And indeed, doctors and health authorities have valuable expertise. But "trust" doesn't mean turning off your critical thinking. The tale of those cigarette ads is an extreme example, yet it underscores a real phenomenon: authority bias. This is the cognitive bias where we assume an authority figure's opinion must be accurate, simply because they're an authority[1][2]. In medicine, authority bias shows up when patients (or even other healthcare workers) uncritically follow the advice of doctors or "experts" – sometimes to their detriment. The expert halo effect can lead to harmful outcomes, like the distribution of unsafe drugs or adherence to outdated practices, just because "Doctor said so"[2].

It's not just individuals – entire institutions can fall prey to authority bias and inertia. Guidelines and recommendations often lag behind the latest science or, worse, get swayed by industry interests. A classic case is how long it took for official bodies to acknowledge the dangers of smoking despite mounting evidence. For years, medical journals even ran tobacco ads because the medical establishment hadn't yet broken free of old assumptions[3][4]. The lesson? We must continually question and investigate health claims, even when they come from authoritative sources.

Consider the modern pharmaceutical industry. There's no question that modern medicine has achieved miracles, from antibiotics to surgical techniques. But it's also true that drug companies are profit-driven entities. Sometimes, their rush to market or desire to maximize sales has led to serious issues – for example, the painkiller Vioxx was heavily promoted before being pulled from the market for heart attack risks. And we've all seen those commercials with dazzling promises, only to be followed by a rapid disclaimer of side effects. As health consumers, relying solely on drug companies' words can be risky. We should consult independent studies, check for biases in research funding, and read the fine print on efficacy and safety.

On the flip side, the booming supplement industry also deserves a discerning eye. Yes, supplements can be incredibly beneficial – many people swear by their daily vitamin, protein powder, or herbal extract. But supplements are big business too, often less regulated than pharmaceuticals. Bold marketing claims ("miracle cure!" "quick fix!") might oversell scant evidence. Just because a product is natural doesn't automatically mean it's effective or safe in high doses. In short, don't blindly trust the label on that bottle from the health store any more than a prescription drug ad. Do your own digging: Has this herb been studied in credible trials? How pure is this product? Is the dosage reasonable? By approaching supplements with the same healthy skepticism as pharmaceuticals, you protect yourself from potential waste or harm.

Finally, let's talk about health authorities and institutions – organizations like the FDA, CDC, or WHO, and even professional associations. These bodies provide invaluable guidance, but they are not infallible. For example, official nutrition guidelines have flip-flopped over the decades (remember when all fats were villainized, only for science to later redeem the avocados and nuts of the world?). Sometimes, guidelines are "dangerously conservative" or outdated because their committees stick to old paradigms or require near-ironclad proof before changing – even when early evidence is compelling[5]. Nutritional recommendations, as we'll explore next, are a prime example. Other times, financial or political pressures play a role. Julian Whitaker, MD, pointed out that the Institute of Medicine (IOM) tends to lowball certain nutrient guidelines, possibly due to an inherent bias against supplements and ties to a conventional "disease care" model[6]. In Dr. Whitaker's colorful words, if a potent nutrient like vitamin D "were a drug, with all the sales clout of the pharmaceutical companies behind it," it would be hailed as the latest wonder – in fact, companies are busy trying to create synthetic (patentable) vitamin D analogs instead[6]. This isn't to say there's a grand conspiracy afoot; it's simply human nature and institutional momentum. The bottom line is no public guideline should be accepted uncritically. Stay curious and compare what independent research says versus what the official word is.

Authority Bias in Action: Learning from History and Experience

Let's ground this in a relatable scenario. You walk into a doctor's office with a minor ailment. The doctor, harried and relying on standard protocols, prescribes a medication. You feel relieved to have an "expert" solution. But later, you recall reading something about that drug's side effects or perhaps a natural alternative. Do you get the prescription filled immediately and follow orders, or do you pause to investigate? It takes courage to question an expert, especially one you respect. Yet asking questions or seeking a second opinion can be lifesaving. Countless patients have found out that a recommended drug was unnecessary, or that a different diet and lifestyle change could work just as well, simply because they researched on their own and looped back with their doctor. A good doctor will welcome your informed questions – and if they don't, that in itself is a red flag that you may be facing an authority bias situation.

We've already looked at one almost absurd historical example – the doctor-endorsed cigarette. It beautifully (or rather, horrifically) illustrates authority bias exploited for profit. Tobacco companies leaned into the public's trust of doctors to sell a harmful product[7][8]. And it worked for a while! People in the 1940s could light up and feel reassured that "if doctors are doing it, it must be okay." Of course, today we shake our heads; the authority bias spell was broken by incontrovertible evidence of harm. But consider: what might be the modern equivalents of this phenomenon? Some critics argue that we see echoes of this dynamic in certain pharmaceutical marketing campaigns or even dietary advice. For example, in the early days of the opioid painkiller push, some authoritative voices downplayed addiction risks – a stance that had devastating consequences once the truth of opioid addiction became clear. Or think of how for years, food industry-funded research muddied the waters about sugar's role in health, while authoritative nutrition guidelines in the 1980s and 1990s focused mainly on cutting fat. Millions of people dutifully switched to low-fat, high-sugar processed foods, thinking they were making a healthy choice, only to see obesity and diabetes rates continue to climb. Authority said one thing; reality turned out to be another.

The key takeaway here isn't to become cynical about every expert or guideline. Rather, it's to appreciate that science is an evolving process, and experts are human. They can be wrong, or biased, or simply working with outdated information. By staying informed and curious – by doing a little independent research – you serve as a double-check on the system. You don't have to become a medical scholar overnight; even simply reading up from reputable sources, comparing recommendations, and understanding basic evidence can elevate you from passive patient to active participant in your health.

RDA: Recommended (or Ridiculous?) Daily Allowances

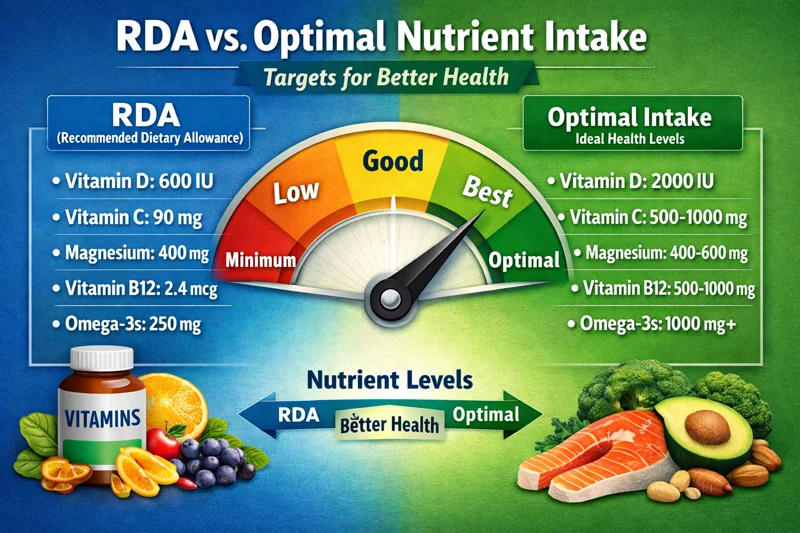

Nowhere is the need for independent scrutiny more evident than in the realm of nutrition, specifically the recommended intakes for vitamins and minerals. The Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA), or in more updated terms RDI (Reference Daily Intake), is supposed to tell us how much of each nutrient a "typically healthy" person needs per day. Sounds straightforward – until you realize that RDAs were mostly designed decades ago and often set just high enough to prevent acute deficiency diseases, but not necessarily high enough for optimal health or chronic disease prevention[9][10]. In other words, the RDA is about avoiding scurvy or rickets, not about feeling truly vibrant.

Researcher and author Bill Sardi has been one of the loudest voices calling RDAs out for being too low. In The New Truth About Vitamins & Minerals, as well as in his articles and commentary, Sardi highlights how millions of people have higher-than-average nutritional needs that the one-size-fits-all RDA doesn't account for[11][12]. Think about it: the RDA assumes a "practically all healthy people" standard – but how many of us are 100% healthy, with no added stresses? If you smoke, you burn through vitamin C faster. If you're under constant stress, your body might need extra B vitamins. If you're pregnant or recovering from an illness, your nutrient requirements shoot up. Sardi points out that a huge swath of the population is on medications that deplete nutrients (from birth control pills to metformin), or dealing with conditions like diabetes or chronic stress, or are elderly with poorer absorption – none of whom are the mythical "healthy 25-year-old" that RDAs were largely based on[11]. "One wonders if the RDA is even relevant in today's society," he quips, noting that it's almost as if nutrient deficiencies are being programmed into the public by keeping recommendations so minimal[13].

Let's look at a concrete example: vitamin C. The current RDA for vitamin C is around 75 mg for women and 90 mg for men – basically, an orange and a half. That dose will prevent scurvy, sure. But is it anywhere near optimal, especially for therapeutic effects like immune support? Many experts say no. Back in 2004, two pharmacology professors, Steve Hickey and Hilary Roberts, published a book arguing that the RDA for vitamin C was built on flawed science and was "indefensible." They pointed out that the body clears vitamin C in about 30 minutes, so testing blood levels hours after a dose (which is how the RDA was determined) hugely underestimates how much we actually might use[14][15]. Hickey and Roberts calculated that to keep blood levels optimal, a person would need at least 2,500 mg of vitamin C spread through the day – nearly 28 times the current RDA![16] They also noted that significant segments of the population (smokers, diabetics, pregnant women, etc.) have higher vitamin C needs that a tiny 75–90 mg cannot satisfy[17]. In fact, even government data show that only about 9% of Americans eat the recommended five servings of fruits and veggies per day (which would give a couple hundred mg of vitamin C), leading the National Cancer Institute to up the recommendation to 9 servings – an implicit admission that earlier "adequate" intakes weren't doing the job[18]. Meanwhile, the upper limit (UL) for vitamin C is set at 2,000 mg, with officials hinting that more could be "toxic," when in reality the main side effect at high doses is loose stools, not organ damage[19]. Our ancestors likely got far more vitamin C from diets rich in wild fruits – estimates suggest they may have consumed the equivalent of 1,800–4,000 mg of vitamin C per day[20]. No wonder the 90 mg recommendation falls short for many people.

Vitamin C is just one example. Consider vitamin D, the sunshine vitamin. The official RDA is 600–800 IU (international units) for adults – again, enough to prevent rickets in most people. But a wave of research in the past two decades has tied higher vitamin D levels to better outcomes in everything from bone health to immune function to mood. Leading researchers often recommend 2,000 IU or more daily for adults, especially in winter[21][22]. Dr. Michael Holick, a foremost expert, argues that even 30 ng/mL in blood is too low a target – he suggests 40–60 ng/mL as optimal, which for many folks means supplementation well above 600 IU[23][24]. Why the disconnect? As Dr. Whitaker observed, the IOM (Institute of Medicine) seemed to focus only on bone health and ignored the myriad other roles of vitamin D, and they clung to a drug-trial level of evidence – basically setting the bar so high that nutrition studies, which often aren't big pharma-funded trials, didn't count[25][26]. Meanwhile, real-world data showed that 87% of patients in one study had vitamin D levels under 32 ng/mL (insufficient by most labs' standards)[27], and global estimates suggest about a billion people are vitamin D deficient or insufficient[28]. When independent groups of scientists reviewed the evidence, they concluded that getting population vitamin D levels into a higher range could slash rates of fractures, cancers, type 1 diabetes, and more – potentially saving billions in healthcare costs[21][22]. In a rather cheeky calculation, Bill Sardi extrapolated those findings to the U.S. and estimated that proper vitamin D supplementation might save $1,346 per person per year in health costs – which adds up to trillions nationwide[29]. Yet, despite such data, the official guidelines remain cautious. This conservative stance, some argue, protects the status quo – it's safer (liability-wise) to under-recommend a nutrient than to over-recommend, and there's not the same profit incentive to champion vitamins as there is for patented drugs[6].

Other nutrients show the same pattern. The RDA for vitamin B12 for adults is a measly 2.4 micrograms, which assumes you efficiently absorb every bit. But many people (especially over age 50) have absorption issues, and some experts recommend or use much higher doses in supplements (100–500 mcg or more) to ensure adequate levels. The RDA for magnesium (~400 mg) might be enough to prevent outright deficiency, yet large portions of the population don't hit that target, and higher intakes are linked with better blood pressure, insulin sensitivity, etc. Zinc is another eye-opener: adult men are advised to get 11 mg and women 8 mg per day. Bill Sardi pointed out that there isn't even a special RDA for seniors who often can't absorb zinc well[30]. We know zinc is crucial for immunity (zinc lozenges can curb colds, for instance) and that even mild zinc deficiency impairs immune response[31][32]. Yet, how often do you hear public health campaigns about getting enough zinc? Sardi noted that despite widespread zinc insufficiency, there's been no major push from health authorities to eradicate it – nothing comparable to the campaigns that eliminated deficiencies like iodine (goiter) or even environmental toxins like lead. "The 'drug model' of disease eradication remains prominent," he says, meaning there's more focus on developing drugs for illnesses than on making sure everyone gets optimal nutrients to prevent illness[33].

All of this isn't to say you should mega-dose nutrients haphazardly. More isn't always better, and every individual has unique needs. But it is to say that the standard nutritional advice might be setting the bar low – aiming for adequacy rather than optimal wellness. The smart approach is to educate yourself: read what cutting-edge research and integrative medicine experts suggest for nutrients that matter to you. If you have a specific health goal, find out if the RDA was just based on avoidance of deficiency and whether higher intakes (within safe limits) have shown added benefits. Discuss these findings with a healthcare provider who is nutrition-savvy. Remember, it's your health, and a little informed questioning can go a long way. As Bill Sardi emphasized, RDAs and government charts are not gospel; they're a starting framework[34][11]. We have the privilege – and responsibility – to dig deeper and tailor our nutritional intake to what helps us thrive, not just survive.

Food as Medicine: Ancient Wisdom Meets Modern Science

One of the core principles of Ancient African Secrets to Great Health is that food is not just fuel – it's medicine. This isn't a new idea; it's ancient wisdom echoed across cultures. "Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food," an adage often attributed to Hippocrates over 2,000 years ago, rings just as true today. But what does it mean in practice, and how is modern science illuminating these age-old truths?

Think about how healing traditions in Africa and around the world evolved. Long before pharmacies and synthetic drugs, people turned to the natural world for remedies. For thousands of years, Africans in diverse regions have used local herbs, roots, bark, and foods to treat illnesses and support health[35]. This knowledge was often passed down through generations in the form of storytelling, apprenticeship, and community practice. In many African cultures, healing wasn't just about the physical body – it was about restoring balance between the body, mind, spirit, and community[36][37]. A healer might give you an herbal potion for your stomach ache, and also perform a calming ritual to address spiritual unrest. While some of the spiritual aspects might lie outside the scope of Western science, the botanical and nutritional aspects are increasingly supported by research.

Modern science is, in a sense, catching up with this traditional knowledge. Plants that were used in folk medicine for centuries are now being studied in labs, and the findings often validate the old uses. A striking example is the Madagascar periwinkle (Catharanthus roseus). Traditional healers used it for various ailments; modern researchers discovered it contains compounds (vinblastine and vincristine) that became powerful chemotherapy drugs for leukemia[38]. The African willow and other plants have yielded anti-malarial and pain-relieving compounds. Or consider the humble willow bark – used in Africa, Europe, and Asia for pain relief since antiquity; it gave us salicylic acid, the precursor to aspirin. Artemisia afra (African wormwood) is a herbal remedy for coughs and malaria in traditional medicine, and it's a cousin of Artemisia annua, from which the modern anti-malarial drug artemisinin was derived. In South Africa, devil's claw (Harpagophytum) has long been used for joint pain; contemporary studies have found it does have anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects useful for arthritis and back pain[39][40]. The African plum (Pygeum africanum) was a folk remedy for urinary problems – today, Pygeum extracts are a well-regarded supplement to help men with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), supported by clinical trials showing improved urinary flow. It's no coincidence that these plants worked; they contain active constituents that, once isolated or concentrated, show measurable benefits.

But you don't need to wait for every grandma's remedy to be dissected in a lab. You can apply the food-as-medicine philosophy in your daily life right now. Start with your plate: every meal is an opportunity to fortify your body. For instance, dark leafy greens, beans, and seeds provide magnesium – a mineral that helps with everything from sleep quality to blood sugar control. Fatty fish, flaxseeds, or chia seeds give you omega-3 fatty acids, nature's anti-inflammatory fats that support brain and heart health. Colorful fruits and veggies are loaded with phytonutrients: tomatoes with lycopene for your prostate, blueberries with anthocyanins for brain and vessel health, and so on. Many spices double as medicinal herbs. Got turmeric in your cupboard? This golden spice is a powerful anti-inflammatory; studies link it to pain relief and improved joint function (just as Ayurvedic and African healing traditions have used turmeric for injuries and arthritis for ages). Garlic doesn't just ward off vampires – it's antibacterial, antiviral, and great for cardiovascular health (traditional Mediterranean and African diets used garlic liberally, and science confirms garlic can modestly improve cholesterol and blood pressure). Ginger, a staple in African tea mixtures and remedies, is fantastic for nausea and digestive upset, as well as muscle soreness relief after exercise – properties confirmed by clinical trials. Even honey, which ancient Egyptians and many African cultures applied to wounds for its healing, is now known to have potent antimicrobial activity and is used in medical-grade wound dressings.

Let's not forget fermented foods, which have a long history in African cuisine (think of naturally fermented porridges or beverages). They provided probiotics and improved nutrition long before we knew the term "probiotics." Now, research on the microbiome shows these foods can boost gut health and immunity. The synergy of a traditional diet – rich in whole plant foods, herbs, and naturally preserved items – is something modern diets often lack, but we can intentionally reincorporate. When you embrace food as medicine, you're essentially merging the best of ancient wisdom with modern know-how: you feed your body nutrients and compounds it evolved to thrive on, and you often preempt disease in the process. After all, it's far better to prevent illness with good food than to treat it with drugs later.

A beautiful aspect of the Ancient African Secrets approach is that it encourages us not only to eat healthy but to reconnect with cultural knowledge and the natural world. It's empowering to realize that, while we have advanced technologies, some of the best healing tools are still the simplest and most accessible: a clove of garlic, a cup of herbal tea, a walk in the sun (for vitamin D and stress reduction), a moment of prayer or meditation to center the spirit. Modern medicine and traditional wisdom are not enemies; they are partners. By valuing both, we gain a more complete toolkit for health.

It's heartening to see that some African countries are integrating traditional medicine with modern healthcare. For example, Ghana has a university program in herbal medicine, and South Africa legally recognizes certain herbal practitioners[42][43]. The World Health Organization has also acknowledged the importance of traditional medicine and called for its safe, evidence-based integration into health systems[44]. All this signals a growing respect: what is old is new again, and the global community is realizing that the elders who knew which bark healed fever or which root eased childbirth had a lot to teach us.

As individuals, we can integrate "food as medicine" by maintaining or rediscovering some of those traditional practices in our own kitchens. Make that soothing ginger-lemon-honey drink your grandmother recommended when you have a cold – and know that ginger's anti-inflammatory gingerols and honey's enzymes are at work. Use moringa leaf (sometimes called the "miracle tree" in parts of Africa) as a powder in your smoothie or soup; it's packed with vitamins, minerals, and protein, and has antioxidant properties. Try hibiscus tea (known as zobo or sobolo in West Africa, karkadé in North/East Africa) for hydration and blood pressure management (science shows hibiscus can help lower hypertension modestly). These are small examples, but the possibilities are endless and enriching. By valuing our food and herbs for their healing potential, we reduce reliance on pills and truly nourish our bodies.

Becoming Your Own Health Researcher – An Empowered Consumer

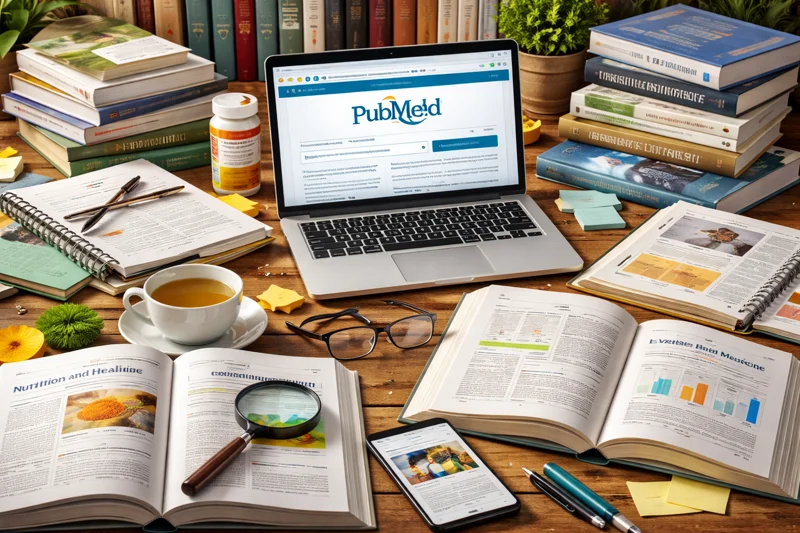

By now, it's clear that doing your own research is not just a cliché – it's a survival skill in the wellness space. But what does that look like in practice for a busy, non-scientist person? It doesn't mean you need to spend hours poring over journals (unless you want to!). It starts with a mindset of curiosity and a willingness to verify. Here are a few practical tips to implement the principles we've discussed:

Ask Questions: For any new drug, supplement, or treatment recommended to you, ask the provider or salesperson: "What is this based on? Are there studies? What are the risks and benefits?" If they can't give a clear answer or if they dismiss your questions, that's a sign you should hit pause and dig deeper on your own.

Use Credible Sources: When researching, not all websites are created equal. Favor sources that are backed by science and have less commercial bias. For example, look at articles on NIH or Mayo Clinic sites, check Wikipedia for an overview (and follow the citations there to actual studies), or use databases like PubMed if you're comfortable reading study abstracts. Also consider authors like Bill Sardi or Dr. Whitaker who, while they have strong viewpoints, often cite scientific literature that you can verify yourself. In this article, we've cited orthomolecular research[45][46], peer-reviewed findings, and authoritative critiques to give you a springboard.

Beware of Authority Bias in Media: Just because a claim is on TV or a popular news site with an MD talking doesn't mean it's the consensus or the whole truth. (Remember the doctor-backed cigarettes – an extreme case, but it underscores the point.) If a headline grabs your attention – "New study says X supplement is worthless" or "Miracle drug Y approved" – read beyond the headline. Often, the actual study is more nuanced, or there may be competing studies with different findings. Try to see if other experts agree or if it's controversial.

Personalize and Experiment (Safely): Independent research isn't only academic; it's also practical. For instance, you might research that magnesium can help sleep. Instead of just taking the RDA amount in a multivitamin, you might experiment (with a doctor's okay) with a higher dose magnesium supplement at night to see if it improves your sleep quality. Track your results. Or if you read that a plant-based diet can improve energy, you could try eating vegetarian for a few weeks and note the effects. Your body is a unique study of one, and paying attention to it is a form of research too. Just ensure you're staying within safe bounds (e.g., don't megadose a vitamin to 50x the upper limit on a whim, or stop a prescribed medication without consulting a professional).

Don't Throw Out the Conventional – Just Enhance It: Doing independent research doesn't mean rejecting doctors or vaccines or prescription drugs outright. It's about complementing and cross-verifying. If you have a great doctor, think of them as a partner – you can bring them what you found, and a good practitioner will discuss it openly. Many doctors actually appreciate well-informed patients (it makes their job easier when you understand the rationale behind a treatment or the importance of a lifestyle change). If your doctor isn't open to discussions, consider why – is it time to get a second opinion? You deserve a voice in your care.

Leverage Ancestral Knowledge: If you come from a family or culture with traditional health practices, cherish that. Do some research on those practices through a modern lens. You might be pleasantly surprised to find scientific studies on that "bitter tea" your mom made you drink or that strange poultice your grandfather used for aches. Even if there's no study yet, using traditional foods and non-harmful remedies can be part of your health repertoire. They connect you to your roots and usually have a low risk profile (e.g., herbs and foods in culinary amounts). As we've discussed, many of these have proven benefits – but even where proof is pending, if it's sensible and safe, you can integrate it with modern approaches.

Lastly, keep in mind that health is holistic. Physical research is vital, but independent research can also mean exploring mental and emotional health avenues. For example, mainstream medicine might offer a drug for anxiety, but your own "research" (and indeed scientific studies) might lead you to try mindfulness meditation, exercise, or counseling as equally important components. Authority bias might have you think only a professional can help, but self-education could empower you to find additional tools like deep-breathing exercises or support groups that dramatically improve your quality of life.

In essence, independent research is about ownership of your health. It's about being an active participant, not a passive recipient. It's about realizing that knowledge is power – the power to ask the right questions, to make informed choices, and to blend the best of all worlds (conventional medicine, traditional remedies, nutrition, and lifestyle) into a plan that works for you.

Conclusion: Bridging Wisdom and Evidence for Great Health

We've journeyed through time and terrain – from vintage cigarette ads to the latest vitamin studies, from ancestral African herb lore to modern kitchen science. The overarching theme is clear: don't blindly trust – thoughtfully verify. By all means, tap into the expertise of doctors, the convenience of pharmacies, and the guidance of public health recommendations. But remember that these sources, while invaluable, are not omniscient. Your own independent research is the secret sauce that ties it all together.

When you take the time to learn and question, you become the hero of your health story. You can catch potential errors (like an unsafe drug or a misdiagnosed deficiency) before they harm you. You can optimize areas of your well-being that might otherwise be neglected (like upping that vitamin D intake to support your immune system during winter, or adding those anti-inflammatory foods to your diet). You also gain confidence – health stops feeling like a mystery controlled by outside forces, and starts feeling like something you have a meaningful say in.

In the spirit of Ancient African Secrets, you also enrich your life by reconnecting with natural remedies and nutrition that have stood the test of time. You're not just popping pills and hoping for the best; you're savoring flavorful foods, nurturing yourself with herbs and spices, and respecting the mind-body-spirit connection that traditional healers have long understood. And now, you're doing it with the blessings of modern science, which more and more "proves" what our ancestors intuitively knew. It's a beautiful synergy of ancient wisdom and modern evidence.

So, as you finish reading this article, I invite you to take action in a small but significant way. Pick one aspect of your health that's been on your mind – maybe your energy levels in the afternoon, or those nagging headaches, or a supplement you've been curious about – and commit to researching it independently. Use the tips and citations provided here as a launchpad. Check the sources we cited (we've linked them throughout this article) and see where they lead. Visit your library or credible websites, ask elders or holistic practitioners for their insights, compare notes, and come to your own informed conclusion. Then, discuss what you learned with a healthcare provider or a knowledgeable friend, and decide on a plan. This plan could be anything from asking your doctor about a possible nutrient deficiency to trying a new bedtime routine based on something you uncovered.

Each step you take in this direction strengthens your "researcher" muscle. Over time, it becomes second nature to read labels, to question headlines, to seek out multiple opinions. You create a personal health culture that honors both science and tradition, reason and intuition. And that is exactly the space where great health flourishes – a space of balance, understanding, and empowerment.

In closing, remember that no one cares about your health more than you do. That's not a cynical statement; it's an empowering one. It means you have the most to gain from seeking truth and the most to lose from remaining in the dark. Drug companies, supplement makers, and even well-meaning doctors operate within systems and incentives that don't always align perfectly with your best interest. By shining your own light of inquiry, you ensure that you won't be led astray by authority bias or incomplete information. Instead, you'll harvest the knowledge and tools you need from all available sources and cultivate your health with wisdom and intention.

Here's to a future where we all combine independent research with community knowledge, where we trust ourselves enough to question authority and trust authority enough when it's earned – a future where ancient secrets and new truths merge to give us the vibrant health we seek. It's not just a dream; it's a path, and you're already on it. Keep asking, keep learning, and may your journey to great health be enriched with both the warmth of stories and the weight of evidence.

Sources

- [1][2] "Authority bias." Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Authority_bias - [3][4][7][8] "Blowing Smoke: Vintage ads of doctors endorsing tobacco." CBS News, Mar. 7, 2012. (Stanford University Tobacco Archive)

https://tobacco.stanford.edu/cigarettes/doctors-smoking/more-doctors-smoke-camels/ - [5][6][10][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29] Whitaker, Julian. "Bogus New Vitamin D Recommendations." Dr. Whitaker's Freedom of Health Foundation, 2012.

https://whitakerhealthfreedom.com/2012/02/bogus-new-vitamin-d-recommendations/ - [9][11][12][13][34] Sardi, Bill. "How Much Nutrition Do You Really Need?" LewRockwell.com, Sep. 23, 2011.

https://www.lewrockwell.com/2011/09/bill-sardi/how-much-nutrition-do-you-really-need/ - [14][15][16][17][18][19] "Researchers Claim RDA for Vitamin C is Flawed." Orthomolecular Medicine News Service, July 7, 2004.

https://omarchives.org/researchers-claim-rda-for-vitamin-c-is-flawed/ - [20][45][46] "Dietary Supplements Under Attack Again – Commentary by Bill Sardi." Orthomolecular.org, Aug. 31, 2018.

https://orthomolecular.org/resources/omns/v14n18.shtml - [30][31][32][33] Sardi, Bill. "The Modern-Day Zinc Deficiency Epidemic." Longevinex, 2013.

https://longevinex.com/modern-day-zinc-deficiency-epidemic/ - [35][36][37][39][40][42][43][47] "Medicinal plants of Africa: Tradition and Future." Alveus Tea Blog, May 5, 2025.

https://www.alveus.eu/blog/african-medicinal-plants/ - [38] "Traditional medicine has a long history of contributing to conventional medicine." World Health Organization

https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/traditional-medicine-has-a-long-history-of-contributing-to-conventional-medicine-and-continues-to-hold-promise - [41] Rack, Kevin. "African Herbs for Asthma – Health and Wellness in Africa (Wiki Loves Africa 2021)." Wikimedia Commons, 2019.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:African_Herbs_for_asthma.jpg - [44] "African traditional medicine." Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/African_traditional_medicine - Ancient African Secrets To Great Health – PeterJohn Fox

Continue exploring

Get the 15-Day Detox Cleanse Planner FREE

Join the newsletter for practical routines and updates.

We respect your privacy. Unsubscribe anytime. No spam, ever.